Be Careful When Explaining House Retirements

April 7, 2020 · 11:05 AM EDT

When now-former Rep. Mark Meadows officially resigned from Congress earlier recently, there wasn’t much shock among the Republican Party. After all, Meadows, known for leading the conservative House Freedom Caucus, had initially stated his intentions to not seek re-election, as he foresaw an increased role in the Trump Administration.

That gamble paid off, because upon handing in his resignation, Meadows could simply walk down Pennsylvania Avenue to a new desk. The reliable Trump ally from North Carolina joined the White House as Chief of Staff, making him now the third representative elected in 2018 who’s leaving Congress early to pursue a different career.

In all fairness, Congressional retirements occur by the dozen every election cycle. Most are for reasons similar to Meadows’: be it personal or professional, representatives choose to decline a subsequent term. Others might forgo incumbency to seek higher office statewide or nationally. Ultimately, though, the total numbers and causes vary year-to-year.

To make sense of 2020 retirements, I posted a preliminary analysis at First Past the Poll last September. At the time, a dominant midterm performance from Democrats led some people to believe swing-district Republicans were exiting out of fear of losing, possibly explaining why four times as many GOP House members had announced plans to not seek re-election.

But ultimately, seat competitiveness wasn’t the strongest justification behind the disproportion. Rather, many retirees had served multiple terms from safer districts, with only a handful of others apparently discouraged by the uphill battle of re-election. From both parties, most retirements were simply just that: retirements...or at least a decision to leave Congress without imminent electoral pressure. And why are more Republicans departing? House members in the minority, dissatisfied with being essentially powerless, perhaps have had a hard time justifying sticking around if they didn’t see a majority on the horizon.

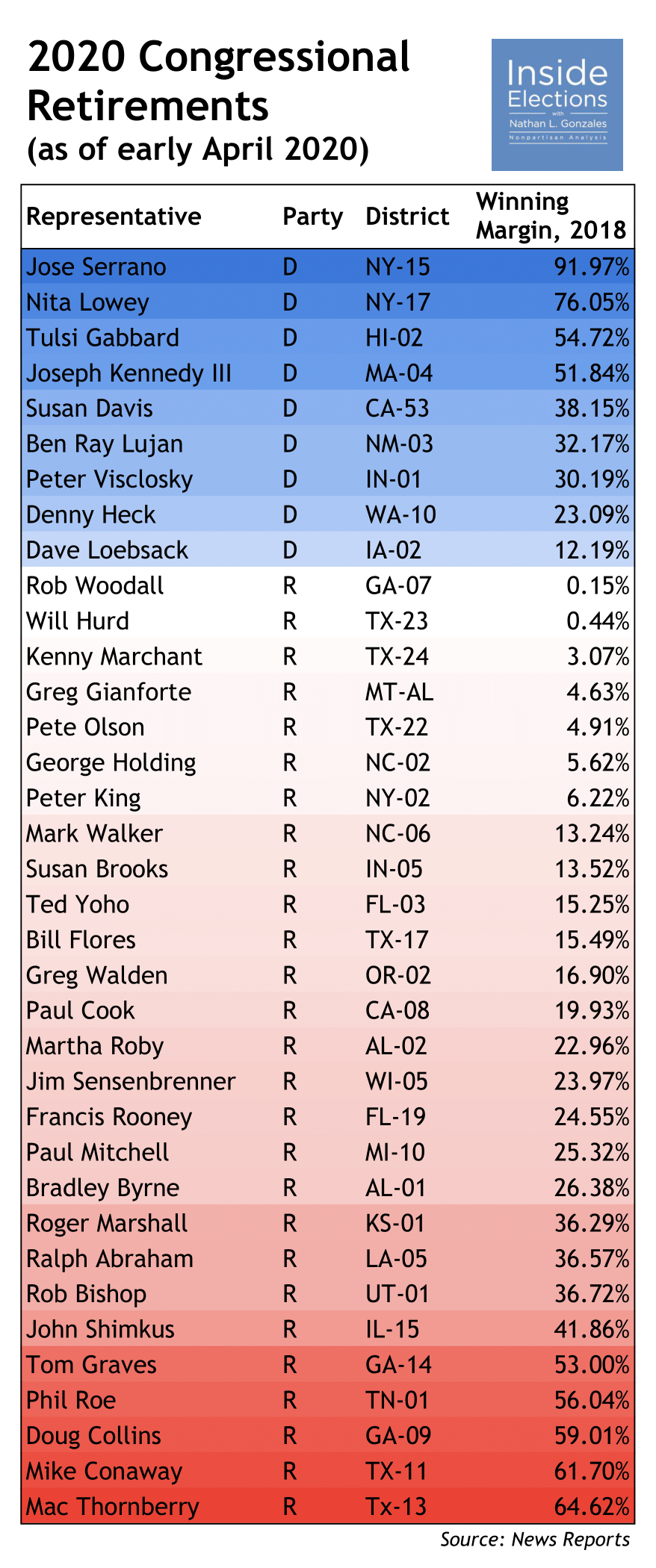

Flash-forward to April, and the situation appears unchanged. According to data collected from news reports and supplemented by the Daily Kos Elections Open Seat Tracker, 36 members of Congress — 27 Republicans and 9 Democrats — have declared plans to retire at the end of this term, as of Monday.

Of those 36, eight are running for another office, such as Joe Kennedy of Massachusetts or Doug Collins of Georgia, while the remaining 28 are by-and-large stepping away from Congress entirely. Not included in these counts are the eight separate Representatives who left early due to death, scandal, or (in the cases of Meadows et al.) personal reasons.

Still, it appears a district’s competitiveness has so far barely influenced the decision to retire before 2020 — between the 28 Representatives who are seemingly gone for good, the average and median 2018 margins of victory were 28 points and 23 points, respectively. Phrased another way, these politicians were not at high risk of losing their seats to begin with.

As always, there are some exceptions: three outgoing Republican members of the Texas delegation are from districts decided by fewer than five percentage points in 2018, as is Republican Rob Woodall from Georgia; Indiana Democrat Pete Visclosky and New York Republican Peter King are two long-serving Congressmen stepping down in increasingly competitive areas; and unfavorable redistricting in North Carolina all but guaranteed withdrawals from Republicans George Holding and Mark Walker.

Even dropouts from districts decided by double digits — such as Republican Susan Brooks, who last won in Indiana by 13 percentage points — might have been influenced by the potential for a more competitive race in a changing district . Notably, Alabama Republican and one-time Trump malcontent Martha Roby is choosing not to run again after a formidable primary challenge two years ago.

The story of spooked representatives retiring en masse is tantalizing, but mostly unfounded. More interesting than the “27 Republicans vs. 9 Democrats” topline is that many of the close seats mentioned above are also currently held by Republicans. Indeed, other metrics similarly suggest a slight GOP disadvantage in the House: with generic ballot aggregates standing at around +8 for Democrats, Republicans (who are defending nearly as many vulnerable districts) could have a difficult time flipping the 18 seats needed for a majority.

Yet at a certain point, one runs the risk of slipping into cherry-picking confirmation bias — Congressional retirements shouldn’t be the go-to stat for forecasting how the House will go in 2020. Still, what tracking them lacks in predictive power, the practice makes up for in case-specific insight; maybe Meadows stepping down tells us less about whether he thinks his party will win, and more about his own political calculus.