No, DC Statehood Won’t Lead to Permanent Senate Majority for Democrats

July 6, 2020 · 10:24 AM EDT

Any conversation about DC statehood will inevitably include Republicans predicting a permanent influx of Democrats on Capitol Hill. But history reveals that two additional Democratic senators would rarely have made a difference in control of the Senate over the last half century.

In late June, the House of Representatives passed a DC statehood bill for the first time in American history. The GOP response to the bill (which is dead on arrival in the Senate) was immediate and furious.

Republicans argued that admitting DC as a state would consign the GOP to permanent minority status in the upper chamber. Arkansas Sen. Tom Cotton said this would “rig the rule of our democracy.” South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham called it “a brazen power grab by the Democratic Party to change the makeup of Congress in a manner that is detrimental to South Carolina.” Idaho Sen. Jim Risch put it simply: if DC (and Puerto Rico) become states, “Republicans will never be in the majority in the United States Senate.”

Putting aside that fact that Puerto Rico is not a reliable Democratic vote since it has sent both Democrats and Republican delegates to Congress over the past two decades, is it true that two additional Democratic senators would preclude Republicans from ever having a majority in the Senate?

With history as a guide, the answer appears to be no: a hypothetical DC statehood would have turned a Republican majority into a Democratic majority for just four months over the past 60 years.

Currently, Republicans hold a 53-47 seat majority. Were DC a state today and represented by two Democrats, Republicans would still hold a 53-49 majority.

In the previous Congress, Republicans held a 52-48 seat majority until the election of Alabama Sen. Doug Jones cut it 51-49. At that point, an additional two Democratic senators would have resulted in a 51-51 split. While it is impossible to say how the parties would have approached a tie (the last time that occurred the parties brokered a power-sharing agreement, but there is no requirement to do so), with a Republican vice president a 51-seat Republican caucus could could control the chamber via tie-breaking vote, however arduous a process that would be.

As a case study, consider the most controversial vote taken by that Senate, the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, which passed 50-48 (Montana Sen. Steve Daines was absent, and Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski agreed to vote “present” instead of “Nay” to cancel out Daines’ absence).

With the addition of two Democratic senators voting “Nay,” the vote would have been 50-50, broken in Kavanuagh’s favor by Vice President Mike Pence. Perhaps in that situation Murkowski would have voted “Nay” instead of “present”, but one must imagine Daines would have returned to Washington were his vote absolutely necessary, resulting in a 51-51 tie, again broken in favor of Kavanaugh.

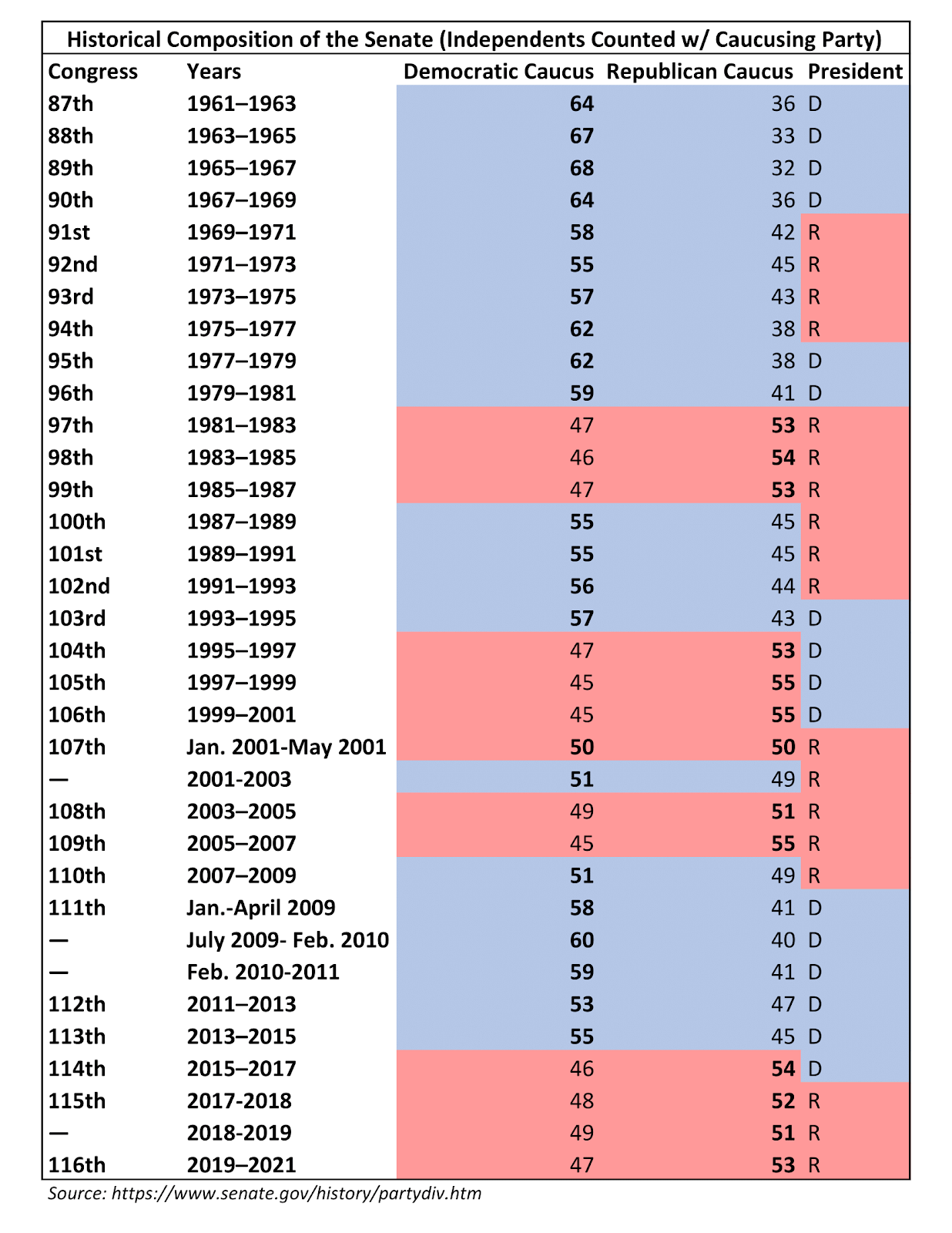

The following table breaks down Senate composition from 1961 onwards — the year the 23rd Amendment, which allocated DC three electoral votes, was adopted. In applicable cases, Independents are categorized by the party with which they caucused. Cells are shaded based on majority control: blue for Democrats, red for Republicans.

By adding two senators to the Demcoratic caucus every Congress (increasing the size of the Senate to 102), we can simulate the effect of DC statehood on control of the Senate.

The table below reflects the hypothetical breakdown of every Senate from 1961 onwards. Notable shifts are highlighted in orange.

As the table illustrates, there is one instance in which an additional two Democratic senators would have caused control of the chamber to switch from Republican to Democratic.

Following the 2000 elections, the Senate was split 50-50. Until January 20, 2001, Democratic Vice President Al Gore served as the tie-breaking vote, giving Democrats a nominal majority. When Republican Vice President Dick Cheney came into office January 20, control reverted to the Republicans. From January 20 until May 24, the two parties operated under an unprecedented power-sharing agreement.

On May 24, Republican Sen. Jim Jeffords of Vermont left his party and became an independent caucusing with the Democrats, giving Democrats a 51-49 majority.

Had the Democratic ranks included two additional senators from DC, they would have begun 2001 with a 52-50 majority, and would not have languished for four months in the minority under the power-sharing arrangement.

There are two other instances in which an additional two Democrats would have altered the balance of power, though in neither would Democrats have actually held the majority. From 2003 to 2005, and again from January of 2018 to January of 2019, Republicans held a 51-49 majority; with DC, it would have been a 51-51 split.

But in both instances, Republicans also controlled the presidency and tie-breaking power, as they did at the beginning of 2001. So despite any power-sharing arrangement, Republicans would have remained the de facto majority party.

An additional two Democratic senators would have had more areas of impact than just determining control of the chamber: in two instances, from 1979 to 1981 and from Feb. 2010-2011, Democrats would have had supermajorities. In the latter, the election of Massachusetts Sen. Scott Brown would not have been the cataclysm it was for Democrats. And there are likely close votes that, depending on the behavior of DC’s senators, could potentially have gone the other way.

All in all, spotting Democrats two additional senators would have changed control of the Senate for all of four months out of 60 years, undermining the GOP’s stated worry on the issue.

Taking a step back, there is no constitutional requirement that DC elect Democrats to the Senate, and nothing that says DC will continue to be as Democratic as it is today — few states look the same politically as they did when they were first admitted to the Union.

It is true that the District is very Democratic now. President Donald Trump received just 4 percent of the vote in 2016, and the high-water mark for Republican performance in the city was President Richard Nixon’s 22 percent in 1972. Trump might sink even lower after sending the military into DC’s streets.

But what if a Republican push for statehood was the beginning of GOP inroads into the city? At a time when support for the Republican Party has fallen to historic lows among African Americans, it might be a smart long-term political move to enfranchise hundreds of thousands of African-American voters, even if in the immediate term it would result in an expanded Democratic caucus.

That DC statehood is so anathema to Republicans suggests that the party isn’t interested in a concerted effort to win back Black voters, particularly in cities. Moreover, Sen. Daines’ implication that DC residents aren’t “real people,” and Sen. Cotton’s insistence that residents of Wyoming (population 578,000, 92.7 percent white) are more deserving of representation than Washingtonians (population 700,000, plurality Black and majority-minority) because they have “well-rounded, working class” jobs like mining and logging, speak to an underlying GOP reticence to recognize Americans in urban areas as legitimate participants of democracy.

So while Republicans continue to concoct reasons to oppose DC representation for partisan purposes, it is simply historically inaccurate to assert that two more Democratic senators would have dramatically changed the balance of power in the past or would automatically do so in the future.